Much of our existing communication about climate change can feel like you’re being lectured at – whether by scientists, climate activists, and fossil fuel executives, they’re always trying to tell you how you should think and what you should be doing better.

But if we’re trying to get a message across and inspire action on climate, one-sided lectures will never work.

We need to be engaging in meaningful climate conversations that recognise diverse perspectives and create space for genuine dialogue.

The problem with one-way climate communications

Climate messaging often falls into the trap of one-sided arguments that fail to engage audiences effectively:

- Scientists using technical jargon and relying on the information deficit model

- Industry narratives that lecture us on individual guilt while deflecting corporate responsibility

- Activist messaging that can appear preachy and media coverage that enforces impossible standards

- Polarisation that deepens divides rather than building bridges for collaborative action.

Let’s examine each of these challenges in more detail.

Scientists and the information deficit model

Climate scientists, whilst being an absolutely vital piece of the puzzle in combating the climate crisis, aren’t always the best communicators.

Whilst statistics and scientific jargon make sense in the context of an academic paper or conference, when this is translated into public engagement campaigns it doesn’t always come across in the best light – often feeling like a literal lecture.

In fact, research has shown that using scientific jargon can significantly reduce the effectiveness of climate communications.

For instance, a 2019 study published in the journal Public Understanding of Science found that “using jargon significantly disrupts processing fluency” and increases resistance to persuasion, heightens risk perceptions, and reduces overall support for technological solutions – even when the jargon is explained. The researchers concluded that “initial messaging should strive to facilitate an easy processing experience and eliminate jargon where possible.”

Susan Joy Hassol, Director of Climate Communication, has identified numerous terms that climate scientists use regularly but that mean something completely different to the general public – terms like “theory,” “aerosols,” “enhance,” and “positive feedback”.

She calls this gap the need to “translate science into English”.

When we’re aiming to engage the public, win their trust, and persuade them of our way of thinking or an action that’s needed, a jargon-filled lecture isn’t the way to go.

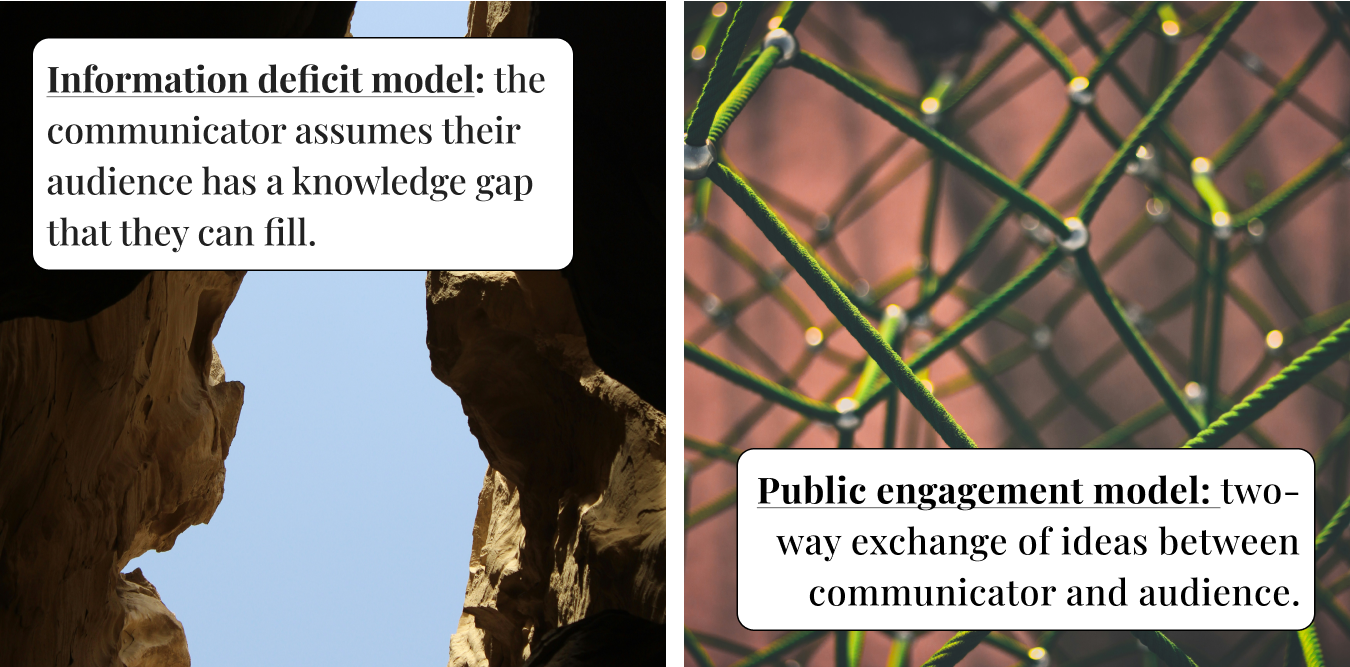

Key concept: What is the information deficit model?

The “information deficit model” in science communication assumes that the public lacks scientific knowledge, and simply providing more information will lead to understanding and behaviour change.

Research shows this approach is largely ineffective, as people interpret information through their existing worldviews, values, and social contexts. Effective climate communication requires more than just facts – it needs dialogue, storytelling, and connection to people’s lived experiences.

Industry narratives and climate guilt

The fossil fuel industry has dominated the narrative on climate change since it first came to light in the 1960s.

Back then it was largely attempts to deny climate science through advertorials and funding researchers to downplay its findings and promote climate scepticism in the mainstream media.

Today, they’ve shifted to placing blame on individuals in their greenwashing ads, another way that climate communications often feels like a lecture.

Infamously, BP created the notion of a ‘carbon footprint’ to guilt-trip people on the carbon emissions resulting from everyday activities – without accounting for their role in extracting and burning fossil fuels, and building a society reliant on them.

More recently, E.On’s advertising campaign ‘It’s Time’ depicts people going about their lives blissfully aware of raging fires, floods, and melting ice caps, with the message that it’s time for us all to do our part – as if individuals hold the key to fixing this mess.

Research consistently shows that guilt and shame-based approaches in climate communication often backfire rather than inspire action.

For instance, a study published in the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics found that climate shame responses often lead to “anger, mocking, denial, and other defensive behaviours” rather than productive engagement with climate solutions.

This aligns with public health communication research by Yale physician Dr. Kristen Panthagani, who demonstrated that shame-based messaging about vaccines entrenched people further in their resistance, with corrections using negative language making recipients more defensive about their beliefs.

Both studies emphasise that approaches focused on connection, empathy, and shared values are more effective than those that provoke shame and guilt.

Key concept: What is climate guilt?

Climate guilt is the feeling of responsibility and shame about one’s contribution to climate change through everyday activities.

While personal actions matter, research shows that excessive focus on individual guilt can be counterproductive, leading to defensiveness or helplessness rather than constructive engagement.

Corporate messaging often leverages climate guilt to shift responsibility away from industry and systemic change onto individuals.

Activism and media polarisation

Climate activists are another key communicator, and whilst their personal style can be highly effective, they can also sometimes come across as morally superior or preachy.

Again it’s the climate guilt and shame that becomes an issue – making people feel they’re being lectured at for everyday choices like eating meat or taking flights, especially when many activists are perceived as coming from privileged backgrounds.

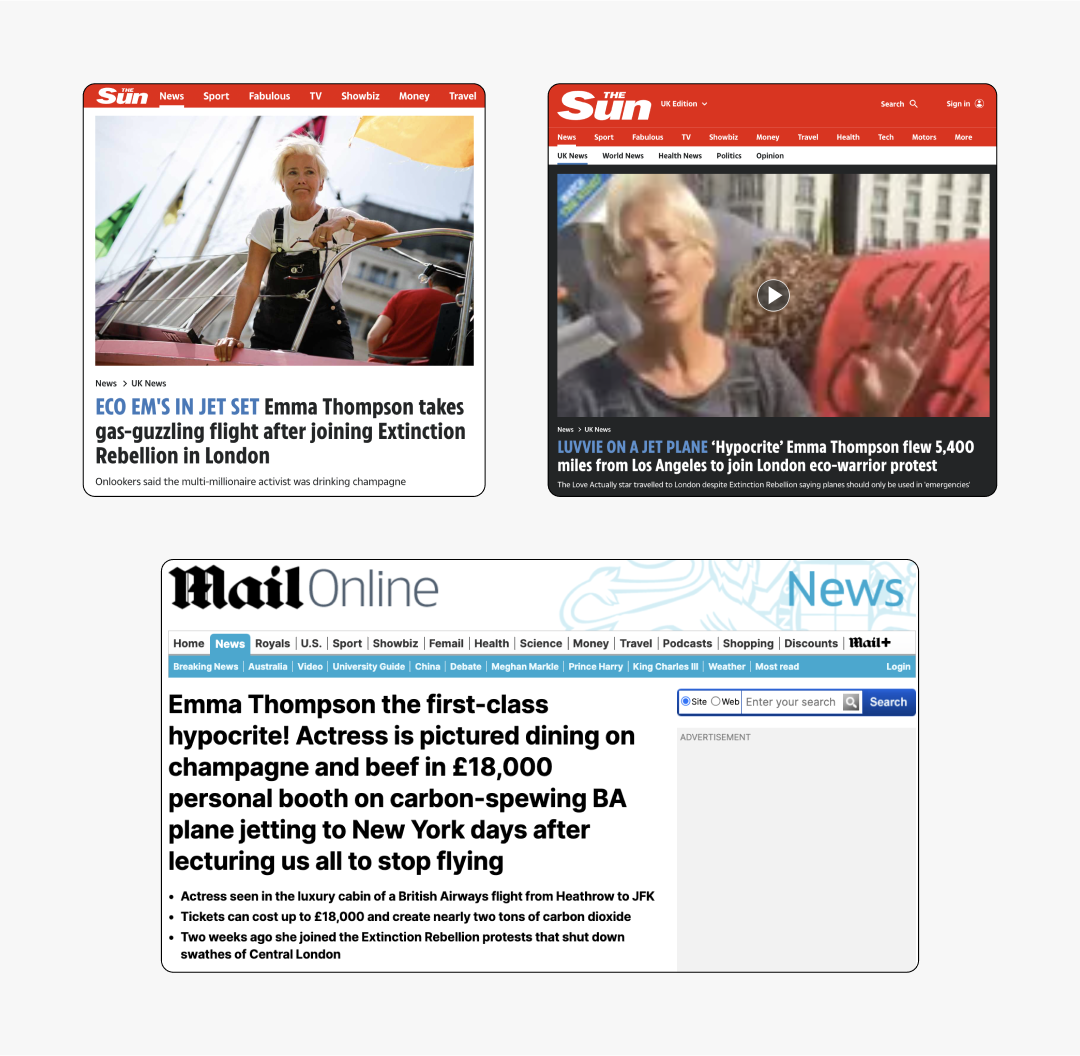

The media often exacerbates this problem by holding anyone who mentions climate action to impossibly high environmental standards.

Like when Emma Thompson attended an Extinction Rebellion protest in London and climate-denying media outlets rushed to point out that she flew from LA to attend:

- ‘Hypocrite’ Emma Thompson flew 5,400 miles from Los Angeles to join London eco-warrior protest

- Emma Thompson the first-class hypocrite!

- Emma Thompson takes gas-guzzling flight after joining Extinction Rebellion in London

- Racking up air miles, Emma Thompson joins climate rebels.

As we’ve seen, shame and guilt aren’t productive emotions when it comes to climate action. In fact, they’re often debilitating – people either get defensive or feel helpless to fix what seems like an overwhelming problem.

‘Us vs you’ lectures about what we, as individuals, should or should not be doing to save the planet only deepen the already existing divides in our increasingly polarised society.

Why two-way climate discussions are more effective

Research consistently shows that dialogue-based approaches to climate communication produce better results than one-way information transfer.

The science behind two-way dialogues for communicating climate change

Multiple studies support the effectiveness of two-way dialogue for science communication:

- A comprehensive review study by Cathelijine Reincke et al found that the deficit model of science communication is largely ineffective, and that enabling two-way dialogue and engagement is hugely beneficial for both parties involved.

- According to research published in the Journal of Science Communication, public engagement with climate science improves significantly when communication moves from a one-way “telling” approach to a two-way dialogue that acknowledges diverse values and perspectives.

- A 2021 study in Environmental Communication found that participatory approaches to climate communication led to greater knowledge retention, higher levels of trust in the information, and increased motivation to take action compared to traditional lecture-style presentations.

As climate scientist Katherine Hayhoe notes in her book “Saving Us”:

“Think of every conversation as being three conversations at once: about facts, feelings, and identity.”

Katherine Hayhoe

Two-way dialogue creates space for all three of those conversations to happen simultaneously – and, importantly, also allows the messenger to gain a better understanding of the worldview and personal factors that go into the audience’s perception of climate change.

“On climate change and other issues with moral implications, we tend to believe that everyone should care for the same self-evident reasons we do. If they don’t, we all too often assume they lack morals. But most people do have morals and are acting according to them; they’re just different from ours. And if we are aware of these differences, we can speak to them.”

Katherine hayhoe

So, with two-way dialogue and conversation-focused climate communications, we can achieve:

- Higher information retention: People remember information better when they’ve actively engaged with it through discussion

- Greater trust in climate science: When people can ask questions and receive clear answers, their trust in the information increases

- More motivation to act: Dialogue that connects climate issues to people’s existing values leads to greater motivation for action

- Community building: Two-way discussions create connections between people concerned about climate change, reducing the sense of isolation.

Key concept: What is ‘public engagement’ in climate change communications?

Public engagement refers to meaningful interaction between scientists, communicators, or policymakers and the general public on climate issues.

Research shows that effective public engagement goes beyond passive information delivery to include active dialogue, collaboration, and co-creation of solutions.

The most successful engagement approaches connect climate issues to community values, provide space for diverse perspectives, and enable participants to see themselves as part of the solution.

Example: How Curious Climate Tasmania use two-way dialogue for effective climate change discussions

The Curious Climate Tasmania group provides an excellent example of effective climate change discussions in action.

This ‘public-powered scientific engagement’ initiative aimed to increase public engagement on climate by flipping traditional one-way science communications on its head.

The group conducted an experimental travelling roadshow, complete with radio show, where members of the public were encouraged to ask questions and open discussions with scientists about their work.

The results demonstrated the power of two-way climate dialogue:

- Hundreds of attendees aged 10-89 turned up to the roadshow events, with 80% saying they were there specifically to talk to scientists

- Attendees left with a high level of trust in the information and research findings discussed at the events

- 93% of attendees said they would like to attend more events.

As the organisers noted:

“People are crying out for relevant and practical climate dialogue with others they can relate to and trust.”

The study also revealed how local context shapes climate conversations.

Attendees from Tasmania’s west coast were interested in extreme climate events due to their history of strong seasonal weather patterns. Meanwhile, discussions started by attendees from the east coast, where many older retirees live in seaside towns, focused on sea-level rise, farming practices, and alternative energy sources.

This highlights the importance of tailoring climate conversations to learn about and lean into the existing worldview and context of a specific audience.

The organisers concluded:

“Such high levels of interest would indicate that our project – engaging with communities on climate change, listening to their concerns and ideas, and working together to identify and develop action options – is one that people desire and need to empower community-level action.”

Sticking with the scientific researcher vs member of public example, for instance, not only will the member of public be more engaged and likely to understand and contextualise the information within their own worldview and identity, but the researcher can actually gain a huge amount of insight from understanding how their research is received and interpreted, and the questions that arise from this.

How to bring two-way climate conversations into your climate campaigns

It can sometimes feel unnerving to put dialogue-based communication into practice.

Some interactions might open your work or your brand up to challenging questions or criticism, but we shouldn’t see this as a negative, only an opportunity to learn and discuss.

For brands engaging in sustainability marketing, open dialogue is especially important.

Climate-engaged audiences face an ongoing battle against greenwashing in the corporate world, as brands like H&M and E.on use large-scale marketing campaigns to state their climate credentials, while shutting down any semblance of conversation or debate about the accuracy of those claims.

Instead, being transparent about your own role or knowledge gaps and enabling dialogue establishes trust – the perfect foundation for effective climate discussions.

Practical steps for better climate discussions

Here are a few practical ways to implement two-way climate dialogue in your communications work:

1. Create space for genuine conversation

- Host interactive events where climate scientists or experts can engage directly with community members

- Use social media for two-way engagement, not just broadcasting information

- Incorporate Q&A sessions into presentations, webinars, and published content

- Create feedback mechanisms like surveys, discussion forums, or comment sections that allow for meaningful exchange.

2. Listen and adapt to your audience

- Conduct audience research to understand existing knowledge, concerns, and values

- Adjust your messaging based on what you learn from your audience

- Acknowledge diverse perspectives and validate different entry points to climate concern

- Follow up on questions and provide additional resources when requested.

3. Make information accessible and relatable

- Use clear, jargon-free language that everyone can understand

- Connect climate issues to local impacts that people can see in their own communities

- Share personal stories about climate experiences and solutions

- Provide practical, actionable steps that feel achievable to your audience.

The evidence is clear: two-way climate conversations are more effective than one-way lectures. By creating space for dialogue, we build trust, deepen understanding, and empower more people to take part in climate action.

Ultimately, climate change impacts us all in different ways, and we all deserve to hold space in the conversation – especially those who have historically lacked a voice in climate discussions.

That means opening up climate communications to enable connections, discussions, debates, criticisms, concerns, questions, and suggestions – we can’t just keep shouting climate messages out into the ether and expecting them to resonate.

When we approach climate communication as a conversation rather than a lecture, we create the conditions for genuine engagement, shared understanding, and collective action.

This article is part of our series on effective climate communication strategies. Read our previous articles on the importance of trusted messengers, reflecting audience worldviews, telling human stories, and incorporating climate hope and positivity.