One major challenge in communicating climate change is that people are prone to interpret climate change as a faraway, abstract problem.

It’s often seen as an “environmental issue” – something to care about only if you’re an eco-warrior or nature-lover who wants to save the animals.

For those who do see the human impacts, it’s still easy to feel like climate change is something that’s causing problems for people in distant countries or future generations, not something that will impact our lives directly.

With this framing, it’s very difficult to get a message across and persuade an audience to act.

So, for climate communication to be effective, it’s vital that we emphasise the personal stories behind climate change, and ideally stories of those that feel close to home.

Why climate change feels distant

When we do think about the human impacts of climate change, it often feels like it will only affect other people, in another place, at another time.

It’s impacting people elsewhere, not those in our local vicinity

In reality, the human effects of climate change are already being felt across the globe with changing weather patterns and extreme weather events increasing in regularity.

However, as someone living in the UK, the general narrative here is that the hotter summers are great, whilst elsewhere the impacts are already deadly – like the heatwaves of 50 degrees in India or the wildfires of LA, or the severe flooding of monsoon seasons in South East Asia.

It’s easy to feel like climate change isn’t going to reach us in our local area.

And it’s that local area that we care about the most.

It’s a psychological fact (via a concept known as place attachment theory) that we all become emotionally attached to the places we live in and visit regularly, like our hometown, holiday destinations, or the local park we visit each week.

What is place attachment theory?

Place attachment theory refers to the emotional bonds that people form with specific geographic locations.

These bonds develop through experiences, memories, and meanings associated with places where we live, grow up, or have meaningful experiences.

When it comes to climate change, place attachment helps explain why people may care deeply about protecting their local environments while feeling less concerned about distant climate impacts.

This localised focus makes climate change feel less urgent because it’s perceived as happening “elsewhere” – unless those distant places also hold personal significance.

Most of these places are physically close to us, which means we naturally care more about protecting our local area than distant parts of the world.

So, even as extreme weather becomes more common globally, until climate change directly affects places we care about, it feels too distant to demand urgent action.

Research published in the journal Global Environmental Change confirms this psychological pattern, finding that people tend to perceive climate impacts as “more severe in developing countries and in more geographically distant zones” than in their own communities. The study found that “self-closeness to an event appears to be related to a greater concern [about that event]”. (Devine-Wright, 2013).

This means that:

- A farmer experiencing changing rainfall patterns first hand feels greater concern than someone reading about rainfall patterns in another country

- Someone whose hometown experienced flooding will likely feel more concerned about climate-induced flooding than someone who’s never lived in a flood zone

- A person with family in a climate-vulnerable region will typically feel more concerned about those specific impacts than someone with no personal connection.

And so on.

Further, a second study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology found that this concept has a direct impact on the likelihood to act on climate change – “individuals who believe climate change impacts are unlikely to happen or will primarily affect other people in other places are less likely to be concerned about climate change impacts and less likely to support climate adaptation” (Singh et al., 2017).

It’s a future problem, not one for right now

Another reason that climate change feels like a distant issue is that humans struggle to act on things that feel like a long-term problem, not an urgent one that will impact us in the short-term.

Again, this is just part of our psychology – with the concept of ‘temporal discounting’ the term used to describe how we place heavier weight on the present than the future.

What is temporal discounting?

Temporal discounting is a psychological concept that describes how humans tend to place greater value on rewards or consequences that are closer to the present, while discounting those that are further in the future.

When it comes to climate change, temporal discounting explains why we often struggle to take urgent action now to prevent disasters that might happen years or decades from now.

Even though the future consequences are severe (like coastal flooding or extreme heat), our brains are wired to prioritise immediate concerns (like economic convenience or lifestyle comfort).

We typically think about this in terms of delayed gratification — like the famous marshmallow test – but it applies to how we prioritise social issues too.

This undervaluing of distant risks has proven to play a significant role in how we perceive climate change risks.

This undervaluing of distant risks has proven to play a significant role in how we perceive climate change risks.

Research into temporal discounting and climate change has yielded compelling evidence that humans consistently prioritise immediate benefits over future consequences.

For instance, a 2009 paper titled “Judgmental Discounting and Environmental Risk Perception” found that people systematically undervalue environmental risks that are distant in time.”

This psychological tendency creates a significant barrier to climate action because the activities contributing to climate change provide immediate, tangible benefits –like the convenience of driving a car – while the costs seem distant and abstract.

It’s an abstract concept that feels intangible

We struggle to visualise what climate change actually is – we can’t see it or touch it, making it feel intangible.

Research published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour identifies this as a key challenge, noting that climate change is often perceived as “abstract, uncertain, and with consequences in distant places or times” (van Lange et al., 2018).

This abstract nature creates yet another psychological barrier to action.

Without tangible evidence that we can see and feel directly, climate change becomes another item on a long list of potential concerns rather than an immediate priority requiring action.

Given that people typically view climate change as a future problem affecting faraway places, it’s incredibly challenging to create climate communication that really breaks through and motivates action.

But there are effective approaches that can help shift this perspective.

Most communications frame climate change as a human issue, not an environmental issue

One of the biggest problems in climate communication is that we’ve made climate change seen primarily as an environmental problem, not a human one.

“They defined climate change as an environmental issue and therefore not a resource, an energy, an economic, a health, or a social rights issue.”

George Marshall, Don’t Even Think About It

This ‘framing’ matters immensely, as George Lakoff explains in his influential work on political communication.

Lakoff, a cognitive linguist, argues that the frames we use – the mental structures that shape how we see the world – determine our understanding of issues like climate change.

What is George Lakoff’s ‘framing’ argument in ‘Don’t Think of an Elephant’?

George Lakoff introduced the concept of framing in political discourse, most notably in his book “Don’t Think of an Elephant!”.

Framing refers to how we use language to shape perception and understanding of issues. Lakoff argues that the words, metaphors, and narratives we use activate certain neural circuits in our brains that influence how we interpret information.

For climate change, Lakoff points out that environmental framing (focusing on “saving the planet” or “polar bears”) disconnects humans from the narrative. This framing makes climate change seem like a special interest issue rather than a human survival issue.

He suggests reframing climate change to emphasise that “we are the polar bears” – highlighting that human existence itself is threatened.

Lakoff’s approach demonstrates why storytelling about real people affected by climate change is so powerful – it reframes climate change from an abstract environmental problem to an immediate human concern that requires action.

Media analysis shows this environmental framing is pervasive in current climate communications.

For instance, one study of climate change imagery found that the most common visuals used in climate communication are polar bears on melting ice, smokestacks, and barren landscapes – all reinforcing the idea that climate change is primarily about “nature” separate from humans (Rebich-Hespanha et al., 2015).

In another study, children frequently mentioned “polar bears melting” as one of their primary associations with climate change (Lee et al., 2020) – suggesting it’s the impacts on animals and on earth’s geography that are most memorable in existing media and climate campaigns.

When climate change is continually framed as an “environmental issue,” it becomes mentally filed away as a special interest concern rather than a human survival issue.

As researcher Saffron O’Neill notes in her study of climate imagery, “The polar bear has become an iconic symbol of climate change… Yet this imagery may distance people from climate change, as polar bears are perceived to be remote from people’s everyday experiences” (O’Neill et al., 2013).

The way we talk about things, the language and images we use, profoundly influences how people understand them.

For decades, climate change has been presented as “saving the planet,” “protecting the environment,” or “fighting global warming” – always with images of melting glaciers and sad polar bears.

The risk to human civilisation is rarely mentioned.

The framing of solutions has been just as problematic.

Lakoff uses the example of carbon taxes. The term “carbon tax” activates images in our minds associated with financial burden, government overreach, and personal sacrifice. This framing makes it easy for opponents to characterise climate action as costly and threatening to economic prosperity.

“It [carbon tax] does not evoke in the minds of the public the real human horrors and economic costs of climate disasters.”

George Lakoff, Don’t Think of an Elephant!

The reality is that climate change is an inherently human issue.

“We are the polar bears. Human existence is threatened, as is the existence of most living beings on earth. When we see the polar bear struggling on the ice floe, that is us.”

George Lakoff, Don’t Think of an Elephant!

Without humans, we wouldn’t be facing climate change in the first place. It’s a problem caused by our industrialisation and use of fossil fuels. And it has very real human consequences too.

The planet has endured dramatic changes in climate in the past. But humans haven’t.

So, what does this mean for how we communicate climate change?

It means that conveying why climate change actually matters for typical people can be hugely powerful – flipping the narrative from an environmental problem to a human one.

“The bottom line is this. To care about climate change, you only need to be one thing, and that’s a person living on planet Earth who wants a better future. Chances are, you’re already that person – and so is everyone else you know.”

Katherine Hayhoe, Saving Us

Framing climate change as the human issue that it is should be woven into any climate change campaign by demonstrating how it impacts things all humans care about: food security, water availability, public health, energy security, and protection of disadvantaged communities – with the specific topics focused on led by the target audience being addressed.

And instead of using scientific language and scare tactics, these topics are better introduced through climate change storytelling that illuminates the real, human stories behind this environmental challenge.

The power of climate change stories: connecting with an audience through human narratives

Research has long shown that stories are powerful as a form of communication.

Humans have a long tradition of storytelling as a way to share information, convey meaning, and connect with other people.

Neuroscience studies have shown that stories provoke real cognitive processes and emotions; even to the point where a listener’s brain waves start to sync with those of the storyteller.

We’re better at remembering stories too – much more effectively than remembering facts, which explains why the statistics which have dominated many climate conversations don’t have the desired impact: they simply don’t stick.

More recently, researchers have shown that storytelling is powerful specifically for communicating about climate change.

A 2020 study at Yale found that sharing personal and emotional stories from people already impacted by climate change had the power to engage even the most skeptical audiences across the political spectrum.

In fact, a personal climate story from a North Carolina sportsman named Richard Mode describing how climate change affected the places he loved to fish was particularly effective at shifting beliefs and risk perceptions, especially among conservatives who are traditionally less receptive to climate messages.

In the study, participants listened to Mode describe in heartfelt tones how he’s seen the climate changing first-hand as ducks migrate later in the year and trout disappear from their old haunts. “Trout require cold, clear, clean water,” Mode explains. “Places that I’ve trout fished in the past that used to hold lots of fish are warming, and the fish just aren’t there like they used to be.” This simple, personal testimony proved remarkably effective at shifting perspectives across political divides.

Plus, stories help to bridge the feeling of distance that often plagues climate communications, as we saw earlier.

According to Yale’s Climate Connections research, “personal stories are particularly powerful because they bridge the psychological distance of climate impacts” and “help us recognize the immediacy of the climate crisis and its impacts” (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2024). This emotional engagement creates the essential foundation for motivating action.

Successful examples of climate storytelling in action

So what do effective climate change stories look like? Let’s take a look at a few examples.

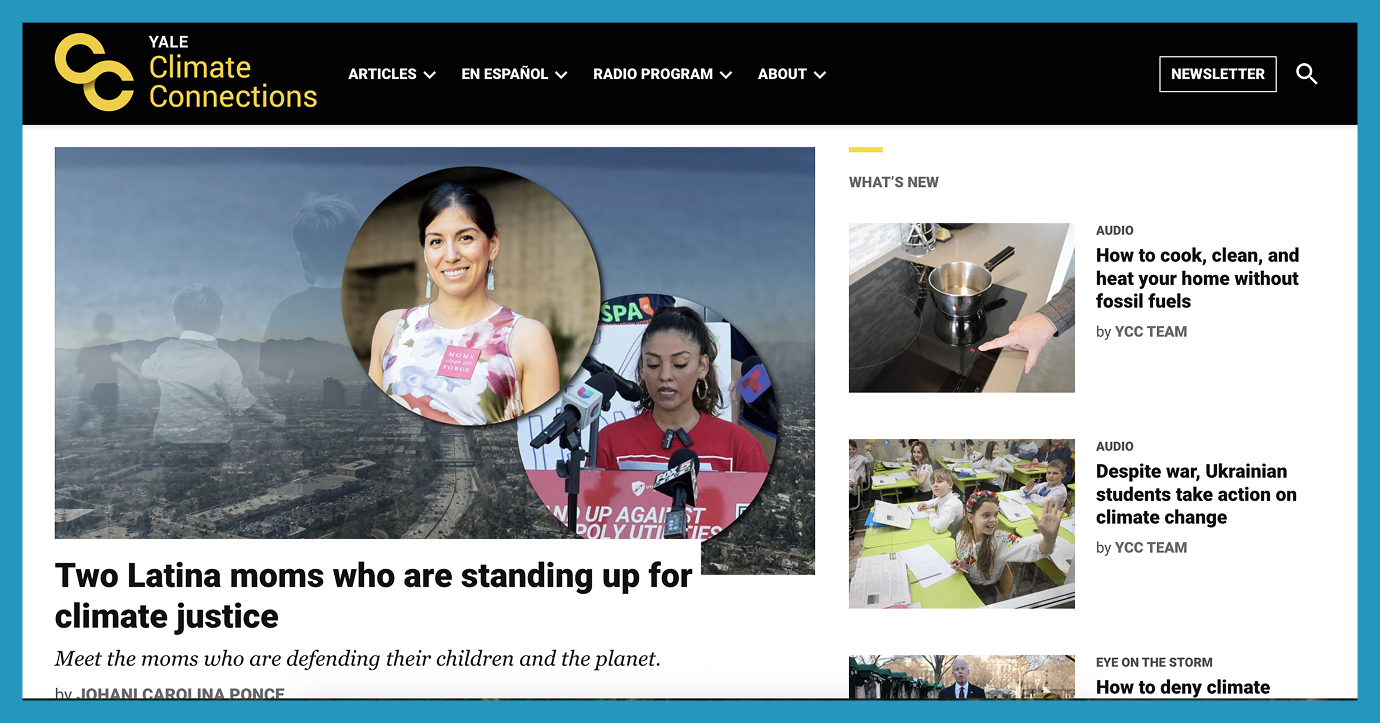

Yale Climate Connections: Everyday voices

Yale Climate Connections (YCC) produces daily 90-second radio stories that feature diverse people talking about how climate change affects their lives and what they’re doing about it.

These stories reach hundreds of radio stations nationwide, including many in conservative areas.

The program connects the dots between climate change events happening to real, relatable people across America, framing climate change as a local as well as global issue.

From pastors preparing their congregations for climate impacts to veterinarians advocating for greater heat protection for racehorses, these stories highlight how climate change affects the people, places, and things their audience already cares about.

Climate Generation’s eyewitness stories

Climate Generation has built a powerful programme around the concept of climate stories.

Founded by polar explorer Will Steger, who has witnessed climate impacts firsthand in Arctic regions, the organisation now collects and shares personal climate stories from people across the country. The organisation also hosts storytelling workshops, helping people discover and share their personal climate change stories – everyone has a story to tell.

Their approach emphasizes that while the climate stories represent individual perspectives, “it is our collective stories that have the power to shift the narrative.”

WaterAid’s climate stories

WaterAid’s series of ‘climate stories’ shows how climate change impacts communities through water-related challenges.

One powerful example focuses on Lake Chilwa in Malawi, which has dried up significantly, affecting local livelihoods – like Samson the fisherman with no fish to sell, or Belita who makes an income selling rice porridge to fishermen but was unable to grow enough crops due to the lack of water.

These stories bring abstract climate impacts down to the human level, showing real consequences for real people trying to support their families.

The “Barrio Fridge” movement

The “Barrio Fridge” started a grassroots movement of community fridges to prevent hunger and reduce food waste simultaneously.

This story demonstrates how local climate solutions can address multiple community needs at once, and how ordinary people can create meaningful change through simple, practical actions.

By sharing these stories of community-led initiatives, climate communicators show that solutions don’t have to wait for top-down policy changes – they can start with neighbors helping neighbours.

How to use climate storytelling to strengthen communication campaigns

As we’ve seen, climate storytelling is perhaps a crucial tool for overcoming psychological distance, ensuring our audiences understand the true human impacts of climate change.

To craft impactful climate stories that motivate action:

- Make it local. Focus on climate stories in places your audience cares about and can relate to. Localised stories that show climate change happening “here, not just there” are more likely to overcome the psychological distance problem.

- Feature diverse voices. Include stories from people your audience identifies with or respects – research shows that trusted messengers within communities are more effective than outside experts.

- Balance impacts with solutions. While it’s important to honestly portray climate impacts, stories that include practical solutions and actions avoid triggering despair. Per Espen Stoknes suggests using the “3:1 rule” — including three hopeful, solution-oriented framings for every one threat.

- Connect to existing values. Frame climate stories around values your audience already holds, whether that’s protecting family, creating jobs, strengthening community, or preserving traditions.

- Emphasise the present, not just the future: Stories should highlight climate impacts happening now, not just those predicted for distant decades, to overcome the psychological distance issue.

This article is part of a series on effective climate change communication. Check out the rest of the series: