Most communication on climate change focuses on the negatives.

There’s the devastating impacts – extreme weather events that are becoming more and more extreme, and more and more frequent, entire species going extinct, corrupt oil and gas executives making millions out of pretending they care.

In ways, that makes sense – the impacts of the climate crisis are already devastating and will only continue to get worse, so there are a lot of negatives to talk about.

Plus, people are more likely to engage with negative headlines, so for media outlets and marketing campaigners who want to maximise engagement, it’s the natural way to go.

But what if this actually damages the effectiveness of the communications when it comes to persuading people to act on climate?

This could well be the case.

There’s a lot of evidence to suggest that instilling climate hope, positivity, and solutions-oriented narratives can be much more persuasive – and that’s what we’ll explore in this article.

Are ‘doom and gloom’ narratives ever effective when communicating climate change?

Doom and gloom narratives do have their place.

The theory of emergency framing (otherwise known as disaster framing) dictates that when issues are shown to be both urgent and exceptional, the audience is more likely to be compelled to act to avoid catastrophe occurring.

There are examples of this negative framing being impactful.

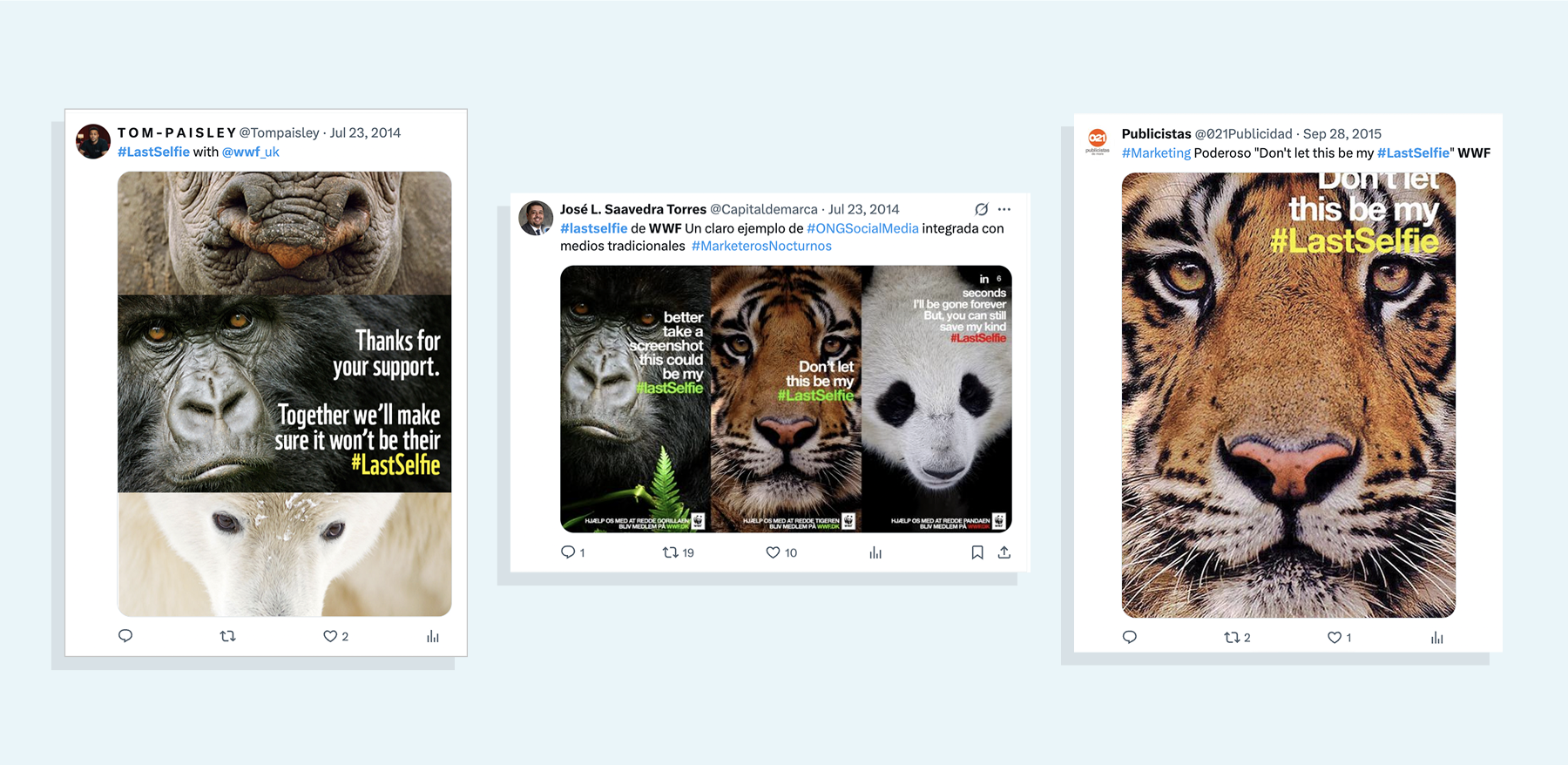

For instance, the World Wildlife Fund has for decades largely centred its campaigns on showcasing animals which are very close to extinction – examples being their ‘love it or lose it’ campaign, removing the panda from their logo, or their ‘#lastselfie’ campaign, all with essentially the same message.

Let’s take a closer look at the #lastselfie campaign as an example.

The #lastselfie campaign aimed to make a viral social media moment on Snapchat, with several WWF accounts sharing images of well-known endangered species, with the message of ‘don’t let this be my last selfie’ – compelling users to act now and pledge a donation to prevent the extinction of the animal.

By focusing on Snapchat as the channel, where the time-bound nature of the platform’s posts meant they disappeared after being viewed for 7 seconds, heightened the sense of urgency around the speed of extinction that we’re seeing today.

After a week of the campaign being live, screenshots of the disappearing snapchats had been shared on Twitter 40,000 times, and WWF had met their monthly donation target. The campaign was also widely recognised for its impact, even winning two awards at the 2015 Webby Awards.

It was clearly an impactful campaign, and there are many more examples of emergency framing being an effective technique when communicating climate change.

However, it isn’t always the case.

The problem with ‘doom and gloom’ narratives for climate communications

Whilst emergency framing and doom and gloom narratives can in some instances drive an audience to act, in many cases they do the exact opposite – prevent action.

Importantly, the whole theory behind ‘emergency framing’ rests on the existence of an urgent and exceptional catastrophe.

There’s no doubt that the climate emergency is this. However, it’s also very much a long-term umbrella catastrophe with lots of catastrophes (extreme weather events, extinctions, etc) happening along the way.

This means that, to be effective, we need to be able to sustain the urgency and exceptional nature of these doom and gloom climate narratives over decades to come.

That’s very difficult to do, because when an issue is in the public eye for a long period, it inevitably loses some of that feeling of immediate urgency – this feeling that climate change will impact future people in other places is one of the huge barriers to action that we face.

Saffron O’Neill and Sophie Nicholson-Cole refer to this as a ‘law of diminishing returns’ in their study “Fear Won’t Do It” for the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research:

“It is possible that a law of diminishing returns may exist. If this exists, fear approaches need to be made more intense as time goes by because of repeated exposure to threatening information in order to produce the same impact on individuals.”

Given that we know that so much existing climate change communication does use this emergency framing, it’s highly likely that its use has already been saturated and is no longer as effective as we’d like it to be.

In fact, a study by the Oxford Institute of Journalism found that “more than 80% of all climate news had employed the disaster frame.”

The doom and gloom narrative is front and centre when communicating climate change.

It’s overwhelming.

And it makes us feel hopeless – because fear is only motivating when we feel it is in our ability to influence change and support solutions to the emergency we’re being told about.

When doom and despair is all we hear, it makes us feel there’s nothing to be done, which is not conducive to persuading an audience to take a desired action.

O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole’s “Fear Won’t Do It” research paper also highlighted the role of control in our psychological functions.

First we seek to control external causes of fear (i.e. take action) and if that is perceived to be impossible (as we see here with climate change) then we seek to control the internal causes instead – which results in “denial and apathy” towards climate change.

“If the external danger—in this case, the impacts of climate change—cannot be controlled (or is not perceived to be controllable), then individuals will attempt to control the internal fear. These internal fear controls, such as issue denial and apathy, can represent barriers to meaningful engagement.”

This suggests that if we persist in relying on disaster framing when communicating climate change, we could unintentionally make the problem worse – driving away engaged audience members who turn instead to denial in the face of hopelessness.

James Patterson et al. sum it up well in their 2021 study ‘The political effects of emergency frames in sustainability’, concluding that whilst emergency framing can be effective, it can als be detrimental to progress.

“Emergency frames can be energising, as witnessed by the diffusion of climate emergency declarations and school student strikes, which can imbue inspiration, hope and a sense of efficacy. But emergency frames can also be emotionally draining and create exhaustion, anxiety, guilt and fear. Fear can have ambiguous and sometimes counterproductive effects on motivation to act.”

So, what’s the alternative?

Narratives of hope, positivity, and climate solutions can be more persuasive

We need hope, because we need climate action.

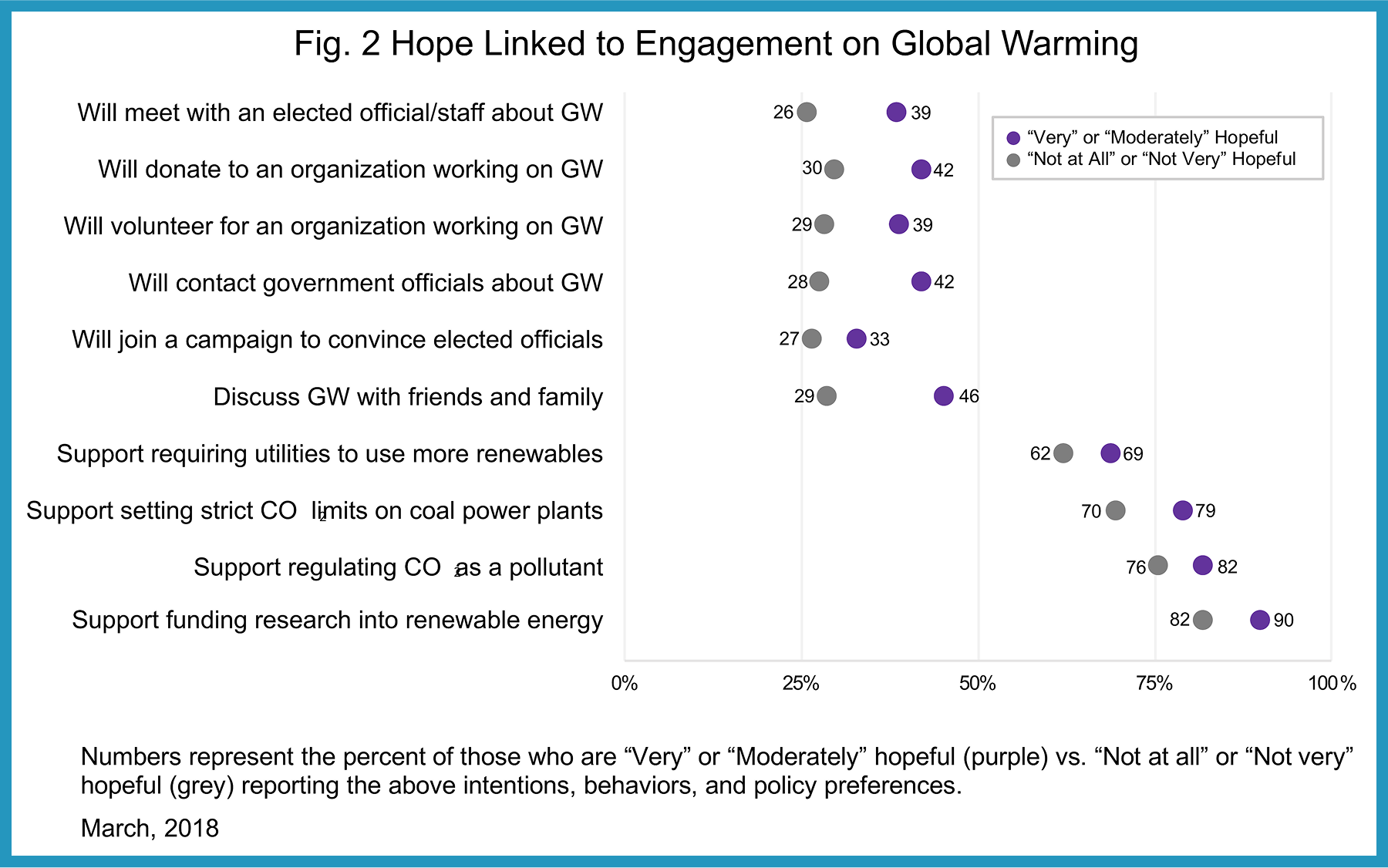

Not only are hopeful people more likely to act themselves, but research from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that people who are hopeful are significantly more likely to try and convince others in their lives to make changes, and to support policies that aim to mitigate climate impacts.

Of course, when we communicate about climate change we should never sugar coat the seriousness of the situation we’re in – it’s simply about creating room within this for actions and solutions that can bring about change.

In fact, a different research study on public engagement by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that creating this balance between showing the negative impacts and leaving room for hope is key to persuading an audience to act.

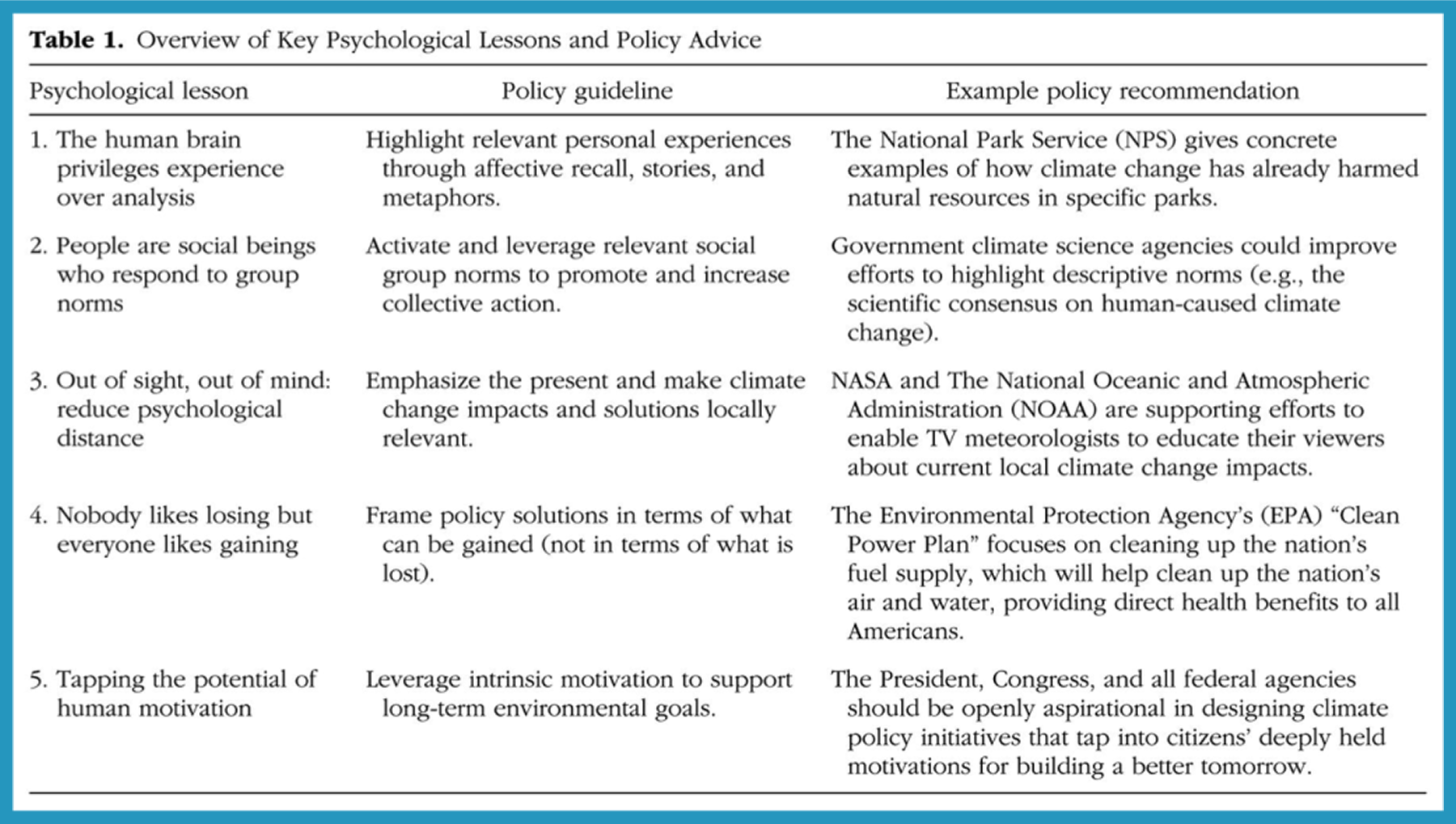

Their findings on the psychological impact of communications suggests that if we want to motivate an audience to act on a problem, we need to highlight:

- Negative: The impact in relation to ourselves and the social groups we identify with

- Negative: The impact in relation to our present and our local area, not a distant future in a faraway place

- Positive: The personal benefits (i.e. what can be gained) of solutions to that problem

- Positive: The ability of the individual to build a better tomorrow through supporting those solutions.

So what can we learn from this to apply to our own climate communications?

Well, firstly, that when we communicate about climate change impacts (whether overall or a specific problem area) we should always emphasise how those impacts relate to the personal and the local for our specific audience.

Secondly, that it’s crucial to then demonstrate potential solutions to those impacts, how those solutions would create a brighter future (greener, fairer, safer, healthier, happier, wealthier) for the things the audience already cares about, and how the audience can take action to support that brighter future.

In Per Espen Stoknes’ book ‘What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming’ he suggests that one effective method is the ‘3:1 rule’ – every time we communicate about climate change, we should include three ‘supportive framings’ for every one ‘threat’ to highlight the wide-reaching benefits of adopting climate solutions, rather than the terrifying impacts of not doing so.

Whatever the approach, the key is to balance out the hopelessness and leave room for action, with visions of climate hope, positivity, and solutions-oriented narratives.

One example of this approach is Grist.

Grist is a non-profit media outlet that is entirely dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and justice – painting the picture of what that brighter future could look like if we embrace climate solutions.

Climate hope, climate positivity, and climate solutions are woven through every article or campaign produced by their brand.

There’s a whole ‘solutions’ section front and centre on their website, where they highlight all the different climate solutions being built and tested.

There’s also the weekly ‘The Beacon’ newsletter – a literal beacon of hope where stories of climate progress are shared to counteract the myriad of negative headlines out there.

And there are bespoke series too, like ‘Imagine 2200’ from 2024, a collection of 1,000 short stories submitted to Grist as part of a competition to celebrate “vivid, hope-filled, diverse visions of climate progress”.

Grist still covers the negative stories, but it’s balanced by the positive.

That balance is the key takeaway that you should take from this article, and apply to your own climate change communications.